The National Lightning Safety Council reports that 11 people were killed by lightning last year.

Three of the deaths reported in 2021 occurred on the job: a 60-year-old construction employee in Wisconsin, a 19-year-old roofer in Florida and a 19-year-old lifeguard in New Jersey.

Although fatalities are rare, the danger is that lightning can strike with little or no warning. That’s why it can’t be ignored or taken lightly by employers or workers—particularly those who spend time outdoors.

“The last time you want to think about doing something about lightning is when it’s actually happening,” said Kevin Beauregard, director of the occupational safety and health division of the North Carolina Department of Labor.

Outdoor workers should practice extra caution during spring and summer. “We want to raise that awareness as we get into the months where these weather events are more prevalent,” said Kevin Cannon, senior director of safety and health services at the Associated General Contractors of America. “It’s about what you need to do to protect yourself.”

Risks and challenges

Occupations that have the highest risk of lightning strikes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, include construction and building maintenance, farming and field labor, heavy equipment operation, logging, pipefitting or plumbing, telecommunications or power utility field repair, and explosives handling/storage.

A direct strike isn’t the only risk to workers. If lightning strikes metal objects, such as pipes used for plumbing and reinforcements for concrete floors and walls, electricity can travel through them. An average strike, according to NWS, is around 300 million volts and about 30,000 amps. A household current is 120 volts and 15 amps.

“It’s something you can significantly decrease your chances of if you take shelter,” Beauregard said. NWS’s lightning safety awareness campaign urges people to go indoors “when thunder roars.”

However, a significant challenge in the construction industry is the numerous settings workers may be in when severe weather strikes. “You have to look at it from the different perspectives of those who are performing work primarily outside, such as civil contractors versus those who are building contractors,” Cannon said. “You may be, at times, working in a fully enclosed building, sometimes partially enclosed, sometimes just framed.”

Many outdoor scenarios include working at height, not only in construction but also telecommunications, utilities, and other industries.

“Say you’re up in a raised position—on a water tower, on top of a tower crane or scaffolding, or on a wind turbine,” Beauregard said. “It’s going to take you time to get down.”

That’s especially important because lightning can strike up to 10 miles from any rainfall, OSHA warns.

Prepare to act

OSHA’s standard on employee emergency action plans (1926.35)—which covers escape procedures and routes, evacuation, and training of workers—applies to lightning.

“An employer can’t control if there’s going to be a lightning strike or not,” Beauregard said. “But what they can control is making sure their employees are properly trained and they know what they should do in the event of an approaching storm or if they find themselves in a storm.” On a jobsite, educating workers about where to go when the threat of lightning rises is imperative.

“That preparation starts with identifying these types of events in your emergency plan, training to it, and then looking at your specific operations—outdoor vs. indoor,” Cannon said.

Oregon OSHA, which operates as a State Plan, says employers can find resources with their state program’s consultation services to help with minimizing, controlling, or eliminating hazards such as lightning strikes.

Among the key steps to stay safe, according to federal OSHA, is checking weather reports. “Prior to starting the work, know what the weather is going to be like that day so you can plan,” Beauregard said

Employers and workers can use cellphone apps—such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s weather app—to track weather conditions. In addition, employees should prepare by “understanding what the policies and procedures entail and put that into action,” Cannon said.

Seeking shelter indoors is the preferred action to avoid being struck by lightning. NOAA recommends doing so in a fully enclosed building with electrical wiring and plumbing, which can conduct electricity more efficiently than your body.

If a building isn’t an option, a hard-topped metal vehicle with its windows rolled up can be a suitable shelter.

Don’t leave any shelter until 30 minutes after hearing the last sound of thunder.

Lightning is most likely to strike the tallest object in an area, so try not to be that tallest object.

However, lying on the ground isn’t recommended—NWS says lying flat “increases your chance of being affected by a potentially deadly ground current.” Similarly, in 2008, the agency stopped recommending people crouch over because “the crouch simply doesn’t provide a significant level of protection.” Instead, use that time to keep searching for shelter.

Workers should stay away from isolated trees, water, utility poles, hilltops, cellphone towers, or large equipment. Instead, retreat to a low-lying area—a valley, a ditch, or an area dense with smaller trees—if shelter isn’t available.

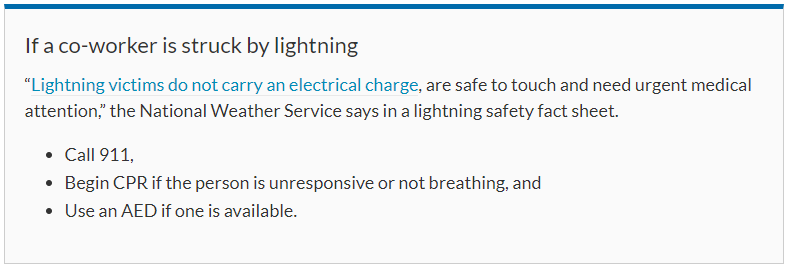

These precautions can help avoid potential serious injuries and death.

“Look at the amount of power in a lightning strike,” Beauregard said. “If you get struck, chances are you’re going to have pretty serious long-lasting injuries.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed